In the latter part of the 20th century, the validity of social sciences became widely accepted. Some branches of social science researchers researched and documented the role of complementary and alternative medicine [CAM] in society. Their actions helped to address the issues of missing data and evidence to support medical claims, which contributed to a rise in their use. Dr. Ernst, the first professor of CAM credits peoples’ belief that CAM is a safer, natural alternative to traditional medicine and the notion that the constraints of regulations in the allopathic medical field prevent practitioners from treating the whole body and encouraging an overall sense of well-being to an increase in use.

Since that time, there have been a number of studies aimed at understanding why people reject or embrace CAM. At the most basic level, many are looking for a treatment that encompasses the whole body, allows them to feel and look good, and produces a complete idea of self to negotiate their identity in society. It has also been suggested that the conceptualization of health is changing, leading to a shift in preferred treatment methods. For example, patients are seeking out ways to become empowered participants in their health, rather than the passive devalued products of the scientific medical community. As people reject the traditional “sick role”, they feel they are establishing themselves as individuals and “voting with their feet” when they seek out alternative forms of treatment. The sick role is:

- The medical view of illness as deviance from the biological norm of health

- The diagnosis of disease results from a correlation of observable symptoms with knowledge about the physiological functioning of the human being

- Involves a social judgment about what is right and proper behavior

Disposable income appears to be one of the most influential factors in the United States, mostly because alternative medicine is not generally covered by health insurance. Many also view CAM as a luxury, rather than a part of their actual healthcare. Individuals in higher socioeconomic brackets are also used to having more resources and therefore control over their lives, enabling them to be more selective in their approach their healthcare. Those with fewer economic resources have a limited number of choices for their healthcare and are not able to consume luxuries and therefore less likely to report CAM use.

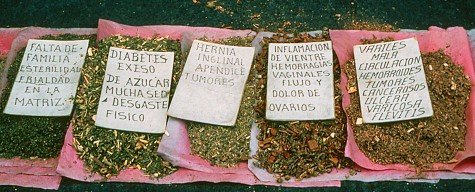

Conversely, there is some evidence showing that people who cannot access “normal” forms of healthcare must use CAM. Others may also opt to reject allopathic medicine because it does not align with their cultural beliefs or because they wish to maintain their cultural heritage. There is also evidence suggesting that members of the non-dominant culture receive subpar care from the biomedical community so they seek out care elsewhere. Those who cite racial discrimination as a reason for their CAM use report that they seek it out to reassert control and self-direction over their health.

An individual or group’s culture and ethnicity also influence the type of CAM used. For example, Blacks and Hispanics are most likely to engage in prayer, Asians are most likely to engage in the use of mind-body interventions and energy therapies, and Whites are most likely to engage in manipulative and body-based therapies. Again, consumption choices are tied to culture. However, individuals who have immigrated to the United States are less likely to consume CAM. There are a number of potential reasons for this, including a lack of exposure to various CAM treatments in their native countries, the cost associated with CAM use, a lack of ability to communicate with healthcare professionals, low utilization of healthcare in general [either because they are healthier than their American natives (which is generally the case) or because they do not have access to CAM]. Immigrants may also believe that medical treatment in America should be provided by the allopathic medical community, especially if they come from a country where allopathic medicine is also dominant.

Gender also influences the consumption of CAM, with women being more likely to use CAM than men. Their reasons are varied and include personal beliefs [which are influenced by (or a lack of) education and disposable income], a lack of results or undesirable side effects from traditional medicine [patient dissatisfaction], doctor recommendations, social influences, and advertising. Hispanic women cite family recommendations their most influential factor; White women cite personal beliefs [often that CAM is more natural], and Black women cite advertising. The issue of advertising influencing the Black community raises public health issues about the reliability of promotional information. This is of particular concern, not only for the Black community but society as a whole, because advertising and fewer regulations from CAM have contributed to a dangerous rise in use:

“The relaxed rules for health claims allowed supplement marketers to target messages to the specific concerns of the 80 million Baby Boomers who, as they reached middle age, became even more interested in self-care, more distrustful of conventional medicine, and more resentful of the increasingly impersonal nature of the managed care health system”.

– Marion Nestle

In the end, however, the factor most strongly influencing CAM use is when an individual suffers from a chronic disease or ailments like back pain, irritable bowel syndrome, a disability, or HIV. Members of this demographic tend to view CAM as a component of self-management of care, a pragmatic approach to living as well as possible, a means to take responsibility for their well-being, and because they recognize a value in the cognitive and attitudinal approach to wellness. However, those who suffer from chronic illness tend not to perceive CAM as an unrealistic means to a cure or as a rejection of allopathic medicine.

sources:

- Grzywacz, J. G., Suerken, C. K., Neiberg, R. H., Lang, W., Bell, R. A., Quandt, S. A., & Arcury, T. A. (2007). Age, Ethnicity, and Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in Health Self-Management. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48(1), 84–98.

- Kronenberg, F., Cushman, L. F., Wade, C. M., Kalmuss, D., & Chao, M. T. (2006). Race/ethnicity and women’s use of complementary and alternative medicine in the United States: results of a national survey. American journal of public health, 96(7), 1236-1242.

- Nestle, M., & Pollan, M. (2013). Food politics: How the food industry influences nutrition and health. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Ong, C. K., Petersen, S., Bodeker, G. C., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2002). Health status of people using complementary and alternative medical practitioner services in 4 English counties. American Journal of Public Health, 92(10), 1653-1656.

- Sointu, E. (2006). The search for wellbeing in alternative and complementary health practices. Sociology of health & illness, 28(3), 330-349.

- Su, D., Li, L., & Pagan, J. A. (2008). Acculturation and the use of complementary and alternative medicine. Social science & medicine, 66(2), 439-453.

image credit:

- themedicalportal.com

- cavsconnect.com

- mexicolore.com.uk

Discover more from Ecosystems United

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “what are the factors influence the use of complementary and alternative medicine?”

Comments are closed.