“If the sick are to reap the full benefit of recent progress in medicine,

a more uniformly arduous and expensive medical education is demanded.”

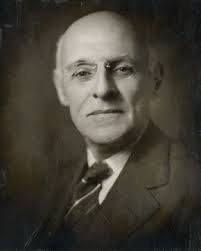

– Abraham Flexner –

Before the standardization of medicine in the United States, medical training was extremely varied and often inadequate. There were three ways that doctors were trained-apprenticeships, through a proprietary education (from doctors who owned the college), or at a university where students participated in a combination of didactic and clinical training at university affiliated hospitals and lecture halls. Each type of education had the potential to teach a variety of medical styles including, but not limited to osteopathy, naturopathy, chiropractic, and homeopathic treatments. However, in was obvious that each of the educations were not equal and there were limited standards for credentialing which meant that medical knowledge and capacity for treatment was extremely varied.

Public opinion and political traditions limited national standardization of medicine despite lobbying efforts by the American Medical Association. This was in part due to the fact that no specific branch of medicine had proven itself more viable than any other and in part that citizens believed that people should have the right to pursue a career in any field they desire through any means that will be accepted by others.

However, around the turn of the century the scientific medical community began to change public opinion by proving the efficacy of scientific methods in topics such as sanitation and vaccination and disproving the efficacy of “heroic methods” such as blistering, bleeding, and purging. These changes prompted the scientific medical community to demand that there be more rigorous and standardized training for medical professionals with an emphasis on applying the scientific method to their everyday activities and engaging students in more hands-on experience and laboratory experiment. As a result, methods that did not conform to these standards were marginalized throughout society.

Building upon this, the AMA established the Council on Medical Education (CME) to promote changing the medical education system. This included standards for entrance to medical school and a standardized curriculum, clinical experience and training in laboratory science, in the program. In order to complete this task, the AMA asked for the help of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (whose president, Henry Pritchett, was a strong advocate for medical school reform) that in turn hired Abraham Flexner to complete the survey of American medical schools.

Throughout 18 months, Flexner visited the 155 medical schools throughout America and examined the following properties of each:

- Size and training of the staff

- Laboratory facilities

- Entrance requirements

- Availability of opportunities in local hospitals

- Financial endowments

His conclusion was that the gap between the best and the worst was extremely vast and that many of these schools claiming to adhere to scientific standards did not have the means – in terms of funds, teachers and resources – to actually do so. In turn, Flexner recommended stopping funding for failing institutions and focus resources on those that had the potential to be the best and most effective. To encourage support of his goals, he had to promote medical education as a means to improving societal status for doctors and as a way to improve public health in order to garner public and government support to diminish the power of proprietary medical schools.

At first the new standards were limited to state regulating boards, but those in favor of changing the standards for medicine argued that licensing practices must be a federal matter as social welfare is linked the quality of the nation’s physicians. The cause gained momentum and eventually wealthy philanthropic groups began donating large sums of money to leading medical universities to promote medical research and education. This ultimately enabled scientific medicine to essentially eradicate proprietary medical schools and establish scientific medicine as the status quo.

It should also be noted that while medical education is now standardized, the changes severely limited the amount of healthcare available economically depressed areas, closed Black medical colleges and reduced the number of poor citizens who could pursue a degree in medicine.

Beck, A. (2004) The Flexner Report and the Standardization of American Medical Education. Journal of the American Medical Association.